The group exhibition Guilty, guilty, guilty! Towards a Feminist Criminology undertakes a feminist assessment of jurisdictional power. The focus is on “women on trial”—female artists, “bad mothers,” women defendants and women plaintiffs on a rather lost cause. In this context, the courtroom does not only appear as a site of legal assessment, but primarily as a space in which a political or ideological image of women is always implicitly negotiated and constructed. What else, beyond the juridical paragraphs, is debated here? And how can we render this hidden discourse visible?

“The face of war is unwomanly” stated journalist Svetlana Alexievich in her a seminal book of the same title1, and the same seems to apply to the juridical history of female delinquency, women’s lawbreaking, and “unlawful” resistance.

As sociologist Carol Smart has argued since the late 1970s, there is striking lack when it comes to assessing a female criminology, and even more so if we dare to think of it as a feminist criminology. To fathom the latter is one of the aims of this project.

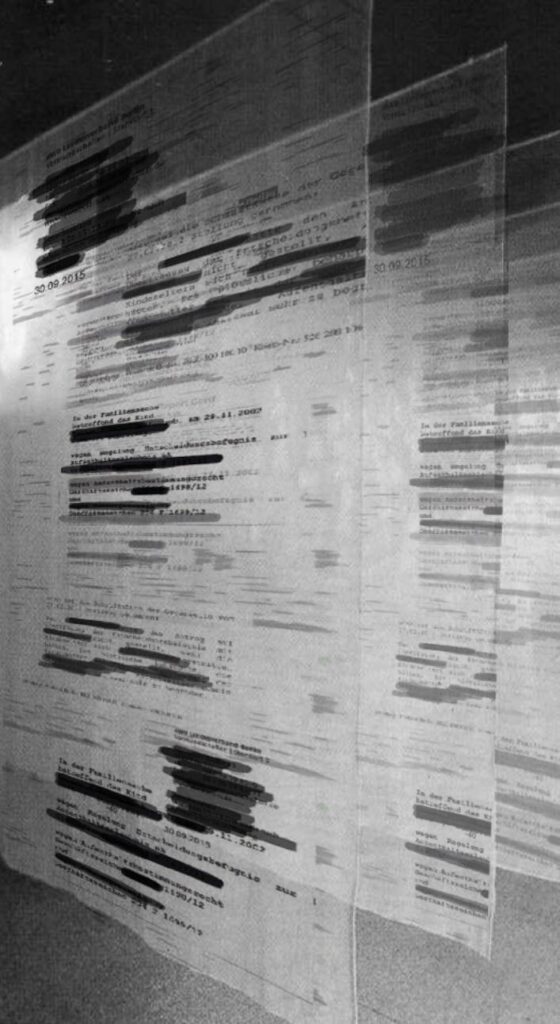

Utilizing a diverse range of methods and forms, including sound, film, collage, installation, research-based works, and activist practices, the artists will navigate through the juridical and bureaucratic sphere, consider alternative evidence, and reflect on double standards. They consider the trials of female concentration camp guards in postwar Germany (Dominique Hurth), the case of a Palestinian underage girl detained at the gateway of an Israeli settlement (Roee Rosen), the fatal stabbing of Marwa El-Sherbini at the Dresden court (Noa Gur), the hunting down of terrorist Patricia Hearst (Dennis Adams), and the precarious conditions of queer youth in American juvenile detention centers (Sam Richardson, Krystal Shelley and Shevaun Wright, conceived by Suzana Milevska). They also address legal constructs of femininity and motherhood (Barbara Breitenfellner, Susanne Sachsse), the distribution of guilt in divorce and child custody trials (Nika Dubrovsky, Ekaterina Shelganova), as well as the particular case of the Zwi Migdal mafia (Galit Eilat). They ultimately and importantly (Rüzgâr Buşki, İpek Duben) consider cases of killings in self-defense—and those who were not able to defend themselves.

The common grounds remain the respective attempt to relocate the conviction of “being guilty” in the social and political conditions. Guilty of murder, or guilty of being alive? Guilty of breaking the law, or guilty of breaking it “unwomanly”?

Guilty, guilty, guilty! Towards a Feminist Criminology responds to these questions in two ways. First, by providing access to a specific stores of “feminist knowledge” of the accused female that is usually excluded from view or silenced in dusty mountains of files. More importantly, by creating a sense of coherence and solidarity between otherwise parceled, uprooted, or assumingly singular incidents of female disobedience—as a major key to a feminist reading of the law.

Exhibition on the Kunstraum Kreuzberg website.

1 Alexievich, Svetlana (1987): Der Krieg hat kein weibliches Gesicht, Berlin: Henschel

2 Smart, Carol (1977): Women, Crime and Criminology: A Feminist Critique, London Boston: Routledge & K. Paul